Ella Fleri Soler, architect at Valentino Architects, writes about one of Malta’s most urgent and visible urban problems – the dominance of cars and car-parking over public space. Working as one half of Text Catalogue (with Andrew Darmanin), together with London-based architect Raffaella Corrieri, the writers collectively explain the supremacy of parking spaces and dual carriageways over public realm in Malta. The writers also provide an overview of a project proposal submitted to the European Commission under the New European Bauhaus initiative, positioning Malta’s blue infrastructure as

a means to integrate public space, providing communities with cycle lanes, pedestrian lanes and elevated areas of leisure.

Finding Meaning in Movement: A Manifesto for a Green Transport Network

The almost two year-long hiatus on life as we knew it put a spotlight on what was thought to be impossible: Maltese roads for the first time in decades lay empty. Without glossing over the genuine struggle that a restriction on movement brings to some tiers of society, this rare and perhaps opportune experience may be the only chance to address a new normal as a strategy to slow climate change. How will we, and indeed, how should we move?

The topic of transport locally is no stranger to heated debates between opposing solutions: metro, tram, rail or mixed modal systems? Multiply bus routes? More car infrastructure? Tunnels? Ferries? Cycling networks? Indeed each potential solution can be assessed on the merits of how best it solves a ‘mechanical’ problem, i.e. how best to carry people from one place to another with the least impactful carbon footprint. What is less spoken about, even overlooked, is that the problem at hand is not an exclusively mechanical one.

A quick excavation through events of much public contention make this immediately clear: The replacement of the old traditional buses for the sleek, bouncier modern ones was quickly met with a hopeful electric bus revival of the bygone yellow aesthetics; the heated debate concerning the Malta-Gozo tunnel vs ferry crossing remains largely driven by the questioned implications on Gozo’s cultural identity; the nostalgic yearning for the old tram system and the re-establishment of the iconic Barrakka lift. All of these events reveal an undeniable cultural tone that transport infrastructure carries by association of individual and collective memory or the identity of communities.

In the context of a dense landscape like Malta, where public space, private development, agricultural land, nature and transport frameworks are so densely intertwined, the cultural implications of infrastructure become obvious and necessarily contentious. Imagine new ferry infrastructure is developed in an area where bathers have been frequenting their entire lives, where the local fishermen work on their nets or berth their fishing vessels and where the elderly sit and chat. The intrusion of the (arguably necessary) ferry infrastructure quashes the day-to-day traditions of the community that inhabits the shore. A ferry stop is gained but a community is lost. The space of transport and the space of communities (and therefore culture) are held in exclusion of each other.

The scenario above has too often been played out in real circumstances and as a result contributes to the notion that infrastructure and people must be mutually exclusive agents – that one must be sacrificed for the other. This schism is at the heart of the conflict between opposing ideas on how Malta should organise its transport needs and served as the starting point for a framework which sees this duality expunged. It is in this spirit that Text Catalogue with Raffaella Corrieri put forward the following short manifesto for the New European Bauhaus’ call for ideas for shaping more beautiful, sustainable and inclusive forms of living together:

MAKE SPACE FOR THE PUBLIC

The typical residential area in most local towns (old or new) is somewhat consistent: building boundary – pavement – carriageway. People’s lives, for the most part, play out within the confines of these zones. More accurately, the stories and traditions of people unfold in the zones where people can physically access and stay put – in this case within the confines of the home and sometimes on the pavement, but less so on carriageways (for obvious reasons).

When accessible space – pavements for example – is taken for carriageways or parking spaces, a society and its daily pulsations are suffocated and its ability for public engagement is choked. People are restricted to move through life in capsules: from the home capsule, to the car capsule, to the office capsule. Space for exchange, interruptions and publicness are eliminated. A caged society is an unwilling society which cannot be expected to move the needle on climate change.

If, however, more space is given to people to access and inhabit – i.e. the carriageway is halved and the pavement is doubled in size – interior life can reassuringly spill out into the (now enlarged) public realm. With this newfound space, society is encouraged to engage with the people and their surroundings in a way that was impossible before: people can walk and chat comfortably side-by-side, children can safely play outside their homes, trees have space to take root and provide shading and life to a once grey street. When people are able to build bonds with their surroundings, society is more willing to protect those spaces from rubbish, crime, and pollution. Space is oxygen for communities and communities become the catalyst for change towards a decarbonised culture.

HACK EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE – a case study

In advocating to surround homes with slow spaces affording public life, how then can space for transit be integrated in a non- capsular manner? If inner-town carriageways are halved, must they be doubled on town outskirts? An answer may lie in the substantial network of ‘invisible’ infrastructure carving through towns offering the potential of unencumbered public access across the island.

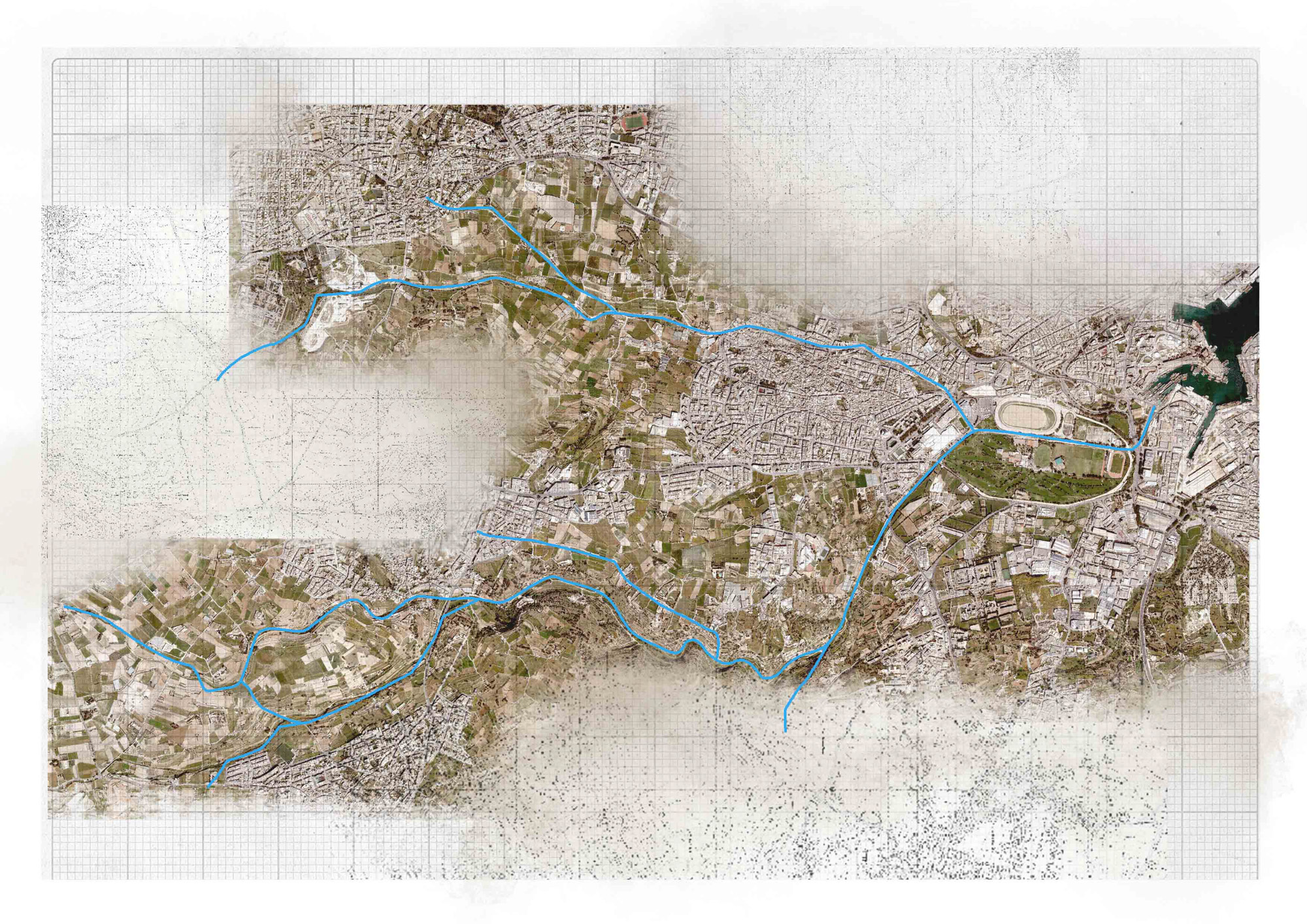

One such system which affords to be hacked for this purpose lies within the island’s blue infrastructure. Malta’s extensive network of storm-water runoff systems divert rainfall out to sea – a reckless strategy for an increasingly arid country. With an average 3,055 hours of sunshine annually, the infrastructure comprising this network is largely idle for a good proportion of the year. What if such runoff networks were to meander people between the centre and the peripheral territories and instead retain that most precious water?

Aside from the obvious opportunity to extend green corridors from the periphery through these water-carrying channels to the heart of towns, this network could further be enhanced to carry cycling lanes, pedestrian routes and elevated areas of leisure so desperately absent from the current urban landscape. The convention for barren and restricted infrastructure development (be it the water, transport, waste or energy sector) can be replaced with new values for an integrated and open infrastructure that invites communities to use and occupy.

CONNECTED NETWORKS FOR CONNECTED COMMUNITIES

It is no coincidence that present subscribers to local public transportation include students, the elderly, migrants, and third- country nationals. This demographic accounts for a growing portion of the local population and for some, the source of much cultural anxiety. Societal fragmentation is not just represented by physical isolation but facilitated by the separation and physical exclusion of communities. Climate change can only amplify this cultural anxiety and class separation.

The closed-loop network of public space and movement infrastructure envisioned in the first two points can ensure the safe and free movement of individuals, especially for isolated communities and individuals of minimal means who would otherwise risk their lives7 or expend too much time or money to get from one place to another. A clean and connected network further encourages new sections of society to participate in public movement networks with demographics it previously would rarely encounter or outright avoid crossing paths with.

A framework that recognises the density of Maltese towns can deploy alternative infrastructure that creates meaning in communities rather than fragments them, and in turn facilitate a smoother transition towards carbon-free living. In giving society the space to thrive and pulsate as it commutes, we may just find that there is joy to be found in the places we least expected them.